IRR is Meaningless: Accurately Comparing Private vs Public Fund Returns

The limitations of IRR and DPI for VC / PE funds, and why hedge funds have it much harder

I recently read an article in The Information that spoke about a certain growth stage venture fund raising a new billion dollar plus fund, how it had beaten the S&P500 by several times in the last decade, and that its 2015 vehicle returned a 27% IRR as of 2023, putting in the second highest quartile, while its DPI (distributed to paid-in) was 1.8x, putting it in the top decile of funds for that vintage.

I have nothing against the fund being profiled, and my point to be made is with regards to the finance industry as a whole. I think there is a lot of bogus flying around in fund return numbers. For one, IRR is meaningless.

Why IRR is Meaningless

Achieving a 27% IRR is not nearly the same thing as achieving a 27% annualized return. IRR is heavily impacted by the timing of cash flows. Let’s use a simple example.

If the venture fund called, hypothetically, $1M of capital in year 5, and distributed double that in year 8, its IRR for that portion of cash flows is about 30%1. But that is not nearly the same as achieving 30% annualized returns. If you put that $1M in the market, and got 30% / yr for eight years, you would have over $8M, about quadruple the amount. On paper, they are both 30%.

And remember, until the fund calls your capital in year 5, you have to hold it in cash ready to give to the fund whenever it calls the capital, so you can’t invest elsewhere during that period. In a hypothetical world where you could actually deploy elsewhere and make use of the opportunity cost of capital, then IRR could make sense.

See here for another example of how IRR goes from 10% to 20% in a hypothetical 1-year investment, where the timing of cash flows is moved by a mere 6 months by using debt to finance the purchase first.

What about DPI?

DPI is the best measure to evaluate a private equity & venture fund’s performance, because it looks at actual cash returned. So let’s look here. The investment fund profiled above in glowing terms is 8 years old, close to the expiry of the fund life, and has a 1.8x DPI. The article states it was a top quartile return. But how does that stack against the S&P 500?

The S&P 500 with dividends reinvested returned 11.5% annualized, or 2.4x in that period, handily beating the 1.8x fund DPI while allowing for full liquidity (where is the illiquidity premium?)

Of course, not reflected in the DPI is the private value remaining in the portfolio companies, which can be significant (this value can be seen with TVPI, total value to paid-in). However, how private investments are marked is quite subjective, making the TVPI a guesstimate. And with the fund close to expiry, it’s hard to say how much of it will become liquid and make its way to increasing the DPI.

Nevertheless, DPI is the best way to compare a private fund’s return with a hedge fund, especially if the private fund has no more TVPI left.

2025 Update

After thinking about it, DPI / MOIC metric doesn’t reward PE firms for early distributions, which are very real and allows LPs to reinvest that capital elsewhere.

Perhaps the best comparison with public markets is adjusting IRR as as if all capital was called at year 0. This somewhat “equalizes” hedge funds’ and PE’s performance by also penalizing the latter for holding cash.

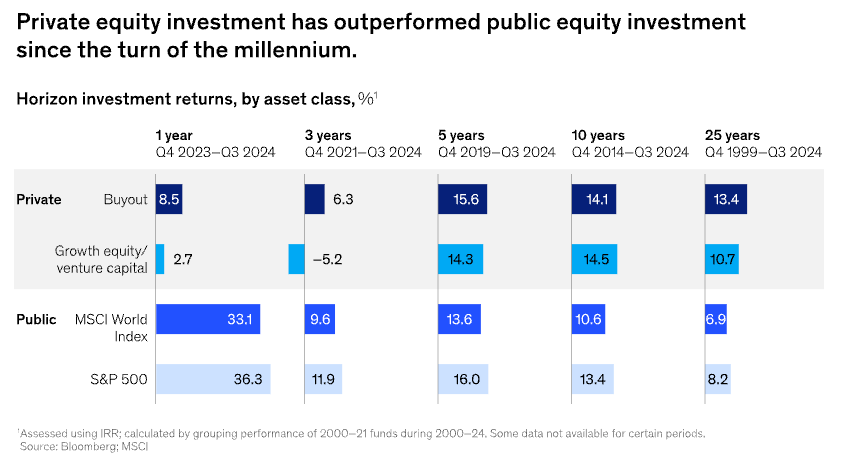

There is also a lot of data that says buyout funds outperform public markets. I'd be curious how such data sources are benchmarking. I would be convinced if they compared the above adjusted IRR to dividend-reinvested S&P annualized returns. My suspicion is that some of this data uses simple IRR as a stand-in for annualized return, which, as this post explains, can be misleading.

I tried a quick google search and the first one I saw is a McKinsey report, and it says "...IRR is still the top-ranked performance metric." And their chart is erroneously comparing S&P returns to IRR (see the chart footnote):

Maybe I’m being too skeptical, but I’ve noticed IRR casually thrown around in conversations and pitch decks as if it’s directly comparable to public market annualized returns. And I wonder if that contributes to the hedge fund underperformance narrative, when that may not actually be the case. I think it's caused by people being mentally lazy. But maybe I'm wrong.

What if Hedge Funds did IRR?

If you’re in industry, you often hear of hedge funds shutting down. In my opinion, hedge funds have it much harder simply because returns are more transparent.

First, they are compared mark to mark with the general indices, so there is no hiding behind illiquid marked-up values.

Second, hedge funds are continuous vehicles. There is no Fund I, II, etc. where one bad fund’s returns can be ignored like in PE / VC funds. How many private investment firms would actually beat the S&P500 if you combined the track record of all of a firm’s funds? Most would be shutting down.

I remember the first small-cap hedge fund I interned at in college had a cumulative 10x return over 20 years after fees (11.4% annualized) tripling the cumulative S&P500 return in the same period (with an amazing founder who was a great teacher). Funds like this that survive long periods are truly impressive. Hedge funds’ performance is being judged cumulatively across all years, unlike private investment funds.

Third, there is no IRR in hedge funds! Imagine a hedge fund didn’t count capital as being deployed while it held cash. Say it deployed and made a 10% return in three months, exited its position, then stayed cash for the rest of the year. Then imagine it stated its annualized return as 46%2! That is pretty much what private funds are doing when they show IRR.

In Summary

Private funds (VC, PE) call capital over years, boosting their IRR, while hedge funds are responsible for managing your capital whether held in cash or not.

Private funds distribute capital upon individual exits, again boosting their IRR, while hedge funds have to manage it even after selling an investment for cash.

Private funds can show higher IRR for many years through the mirage of illiquid values. Second, if a fund performs badly, performance resets with the next fund. Hedge funds don’t have either benefit.

But?

One may ask: Are hedge funds get compensated more for the above factors?

Yes and no.

No, hedge funds are not compensated more: In the first half of private fund’s life (say 5 years out of 10) the fund will charge management fees (often 2%) on committed capital even as the capital is waiting to be called. So they are getting compensated just like hedge funds despite not “managing” the capital.

And remember, as a LP, you can’t do anything else with the cash committed because it must stand ready to be called.

Yes, hedge funds are compensated more: In the latter half of the PE fund’s life, management fees are only charged on invested capital. Whereas hedge funds continue to charge management fees on the entire AUM.

Neutral: Private funds don’t earn performance fees on IRR, they earn it on distributed capital, which takes time. So private funds look good on paper with IRR, but as Howard Marks once said, “You can’t eat IRR.” (at least not directly. But it can help them raise the next fund). Hedge funds earn it immediately because it’s liquid.

So yes, hedge funds earn faster and larger fees due to liquidity and not distributing the capital back. On the flip side, they are always subject to redemption, vs private funds that have capital locked up for 10 years.

My main point is that private funds have it better because the average allocator does not fully recognize how much more a private funds’ performance is boosted vs that of hedge funds because our brains like to simplify, and we implicitly take IRR ~= annual return.

Buffett’s Partnership Era is Astounding

When Buffett ran his partnership (BPL) from 1957 - 1968, he compounded at 31.6% (25.3% after fees) vs the Dow’s 9.1%. Over 12 years, that was 15x for BPL vs 2.8x for the Dow. He also 1) charged no management fee, 2) a guaranteed 4% interest rate to limited partners that carried forward if he failed to provide that, and 3) 25% carry on the gains above the 4%.

Buffett was paranoid about being fair to his partners, and invested his personal money in the exact same positions (he was the largest investor in BPL within a couple of years). It’s rare to find an investor to give up so much in fees, and be that transparent and overly fair, and can still beat the market handily when most funds fail to do that.

Do Hedge Funds Provide Societal Value?

I saw the movie Dumb Money with my partner, and we pondered this question. My argument is yes, and I find it interesting what Ken Griffin of Citadel says here about high frequency trading firms.

His argument was that HFT increases liquidity, and increasing liquidity brings down the cost of capital for corporate America. Paraphrasing his points:

Institutional investors think about days of traded volume (“I’ll own 5 days of traded volume”). It’s used as a proxy for how difficult it is to get into or out of a position. Everybody thinks about and values liquidity.

HFT creates trading volume, that creates liquidity for real money players (Capital Research, T Rowe, Fidelity) to rebalance their portfolio. This really matters when companies go to raise capital. If a stock is liquid, it’s very easy to do a stock secondary to raise money. A stock that’s illiquid - you’re not getting that deal.

It’s incredibly positive for society that we have the deepest, most liquid capital market in the world.

“Let’s tie that back to the students in this room. When you have a successful startup, you have to convince VCs to give you that check. If they believe they can go public with that idea, you’ll get that check. But if our public markets aren’t liquid, the capital cannot be raised. You won’t get that check from the VC.”

It’s one very large flywheel that makes capitalism work in America.

Then he gives the counterfactual, Europe:

Phenomenal schools, well educated population, their capital markets is much smaller than US as a % of economic activity. In the US, 80% of all corporate debt is provided by capital markets. In Europe, it’s 20% capital markets, 80% banks. High yield finance, Drexel, etc origin story in the U.S.

“Name ten startups of note in Europe over the last 25 years. You can name a few, but it’s hard. In the US, I can name one after another.”

“Our capital markets are an incredibly important part of what makes our economy work. That ability to have liquidity, which is created by today’s market makers, is an important integral part of this entire system that makes the United States the leader in the world in new corporate formation, innovation, and the great success stories from Google to Apple that are at best copied around the world.”

While Ken was speaking about high frequency trading / market making, this obviously applies to hedge funds. Other aspects to note are that hedge funds’ “search” for a company’s fair market value has real implications on a company’s ability to use stock to make acquisitions, raise capital, pay employees, or sell for cash to invest in operations. Hedge funds can also short a company that may be committing fraud or otherwise doesn’t deserve a lofty valuation. As Ken says, it’s all part of a large flywheel that makes capitalism work.

1M *1.3^3 = 2.1

1.1^4-1 = 0.4641 = 46.41%

Excellent article and very clearly written analysis. This is just not widely known.